The Friends and Family Guide to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic -- Supplemental Material

Highlights, supplementary material and updates from The Friend and Family Guide to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic by Peter Canning, to be published August 26, 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Who is at Risk?

Source: Today I Matter

Today anyone who uses illicit opioids or pills not directly prescribed to them by a doctor is at risk for overdosing. This includes both experienced users and those using for the first time. Our current street drug supply is toxic, poison. No one who uses these drugs is safe.

Using Alone:

The number one risk factor for dying of a fatal overdose is using opioids alone. Ninety-one percent of all fatal opioid overdoses in 2021 were unwitnessed.

One Use Can Kill

A person doesn't have to be addicted to opioids to accidentally overdose on them. While people addicted to opioids are at a higher risk for overdose because they use more often than people who are not addicted, no one is safe.

Opportunity for Intervention

According to the CDC, in 2021, 65% of people who died of fatal overdose had a potential opportunity for intervention before their deaths, including interaction with mental health or substance use treatment, recent release from prison, or potential person in the area who could have delivered naloxone had they known the person was overdosing in a nearby room or other accessible space.

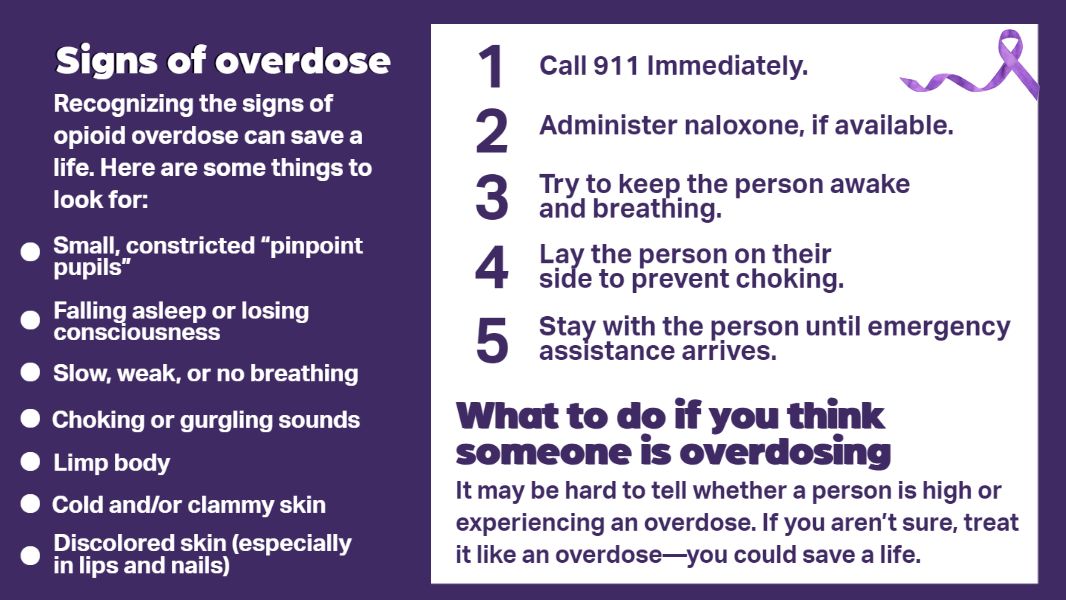

How to Recognize Overdose

Every citizen should learn to quickly recognize an opioid overdose and take the necessary steps to reverse the overdose and save a life of a loved one or a stranger.

Graphic: SAMSA

Signs of Opioid Use

Pinpoint Pupils:

One of the telltale signs of opioid use is constricted or pinpoint pupils, also known as miosis. The pupil is the dot in the center of your eye. Opioids act on the eyes' pupillary response. Most other drugs as well as alcohol cause dilated or larger pupils. While there are many factors that affect pupillary response, if a person with a history of opioid use has pinpoint pupils, they are likely under the influence of opioids. Pinpoint pupils alone are only signs of possible opioid use, not overdose. An overdose begins when the drug exceeds its intended effects and impairs consciousness and breathing.

Stupor:

Opioids produce euphoria, intense feelings of happiness and well-being. They can also produce stupor, a deep lethargy and near unconsciousness that requires stimulation to be aroused from. It is not uncommon to find people on opioids to be "on the nod." They are breathing and may be standing or sitting with their heads slumped forward as if they have nodded off to sleep. For some this depressed consciousness state is not an overdose, but often the intended outcome, the feeling the user sought when taking the drug. People "on the nod" are still breathing adequately and often can be roused with a simple shake.

Signs of Opioid Overdose

Unconsciousness:

Depressed consciousness, which can precede or accompany decreased breathing, may lead to unconsciousness. One of the dangers of unconsciousness is that a person may accidentally occlude their airway with their tongue, or if they bend their neck too much, it can prevent them from taking in air. Snoring may be heard from an overdosed patient when their tongue partially blocks the airway. Opioids can also depress the gag reflex making it hard for a person who is still breathing to protect their lungs from secretions and vomit, causing them to choke to death.

Decreased Respirations/Cyanosis/Apnea:

Opioids produce slowed respirations (breathing). When respirations become inadequate, skin color changes as cyanosis develops from lack of oxygen. This is often first noticed around the lips and in the fingers as they develop a bluish tint. Overdose can present as gurgling, snoring, irregular, shallow or eventually absent breathing (apnea).

How to Respond to an Overdose

When you suspect an unconscious person is suffering from an opioid overdose, the first thing you do is try to stimulate the patient. Often stimulation alone will restore breathing and consciousness. Shake the person's shoulder while calling their name. If that doesn't immediately work, rub your knuckles hard against their sternum (breastbone). This is painful but can elicit a response. If you can lay the person on their side, do so. Whether on the ground or sitting up, make certain their head is tilted back so they are not blocking their airway.

To determine if a person is breathing, look for chest rise or check to see if any air is coming out of the person's nose or mouth.

If a person is not breathing and you can't feel a pulse, you should start CPR.

If a person has a pulse and is breathing adequately, but is not responsive, roll them onto their side to prevent them from choking if they vomit.

If a person has a pulse, but is breathing inadequately despite stimulation, this person should receive naloxoner.

Call 911 as soon as possible.

Source: CDC

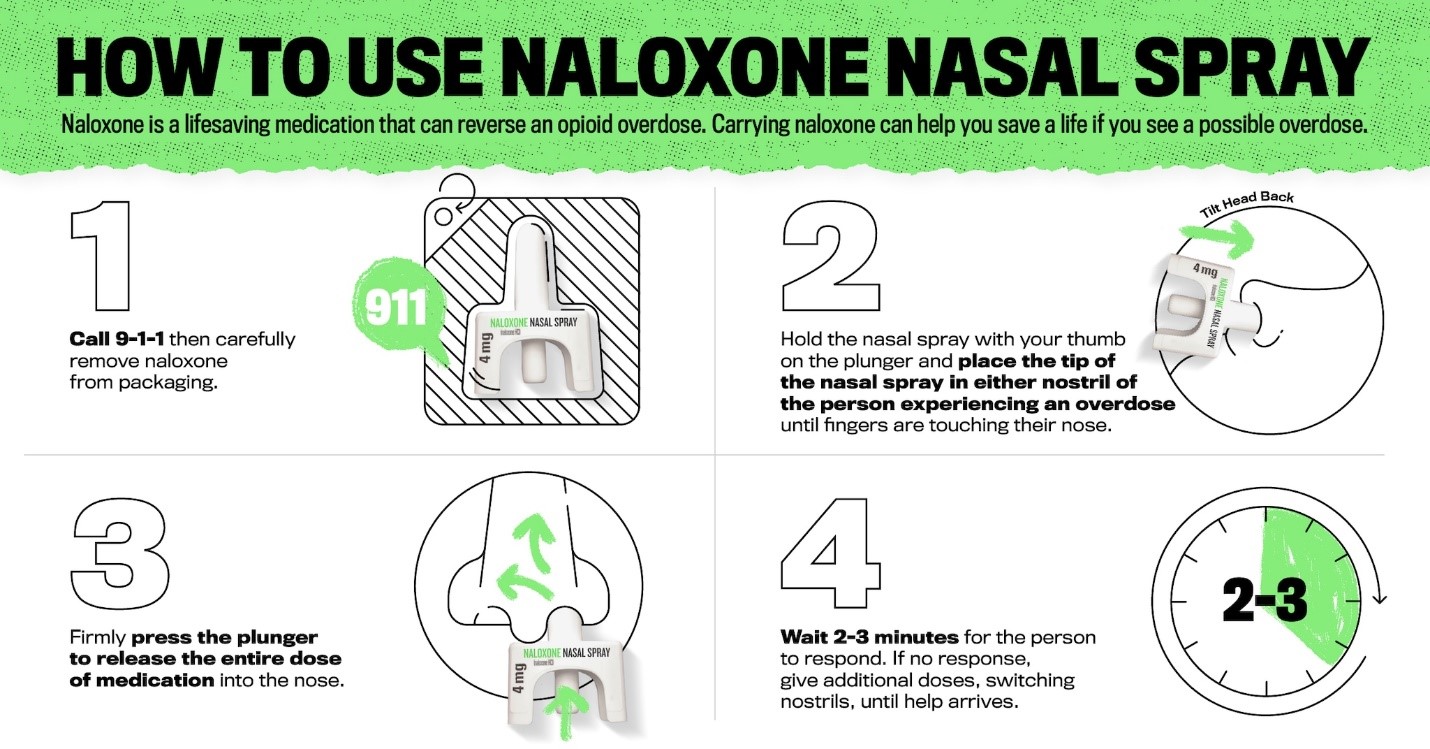

Naloxone

Naloxone (an opioid antagonist) reverses the effects of opioids on our respiratory system. Naloxone has a stronger affinity for the brain's breathing receptors (the mu receptors) than opioids do.

Naloxone knocks opioids off the receptors, enabling a person to resume breathing. Naloxone does not work on non-opioid drugs such as benzodiazepines, cocaine, methamphetamines, or alcohol, but since these drugs are often used in combination with opioids, the naloxone will reverse the opioid contribution to the overdose--the slowing or cessation of breathing--the symptom most likely to cause death.

Intranasal Spray

The intranasal spray is the most common form of naloxone available to the public and the easiest to use, but it is the slowest to take effect. It is FDA approved and specifically formulated for intranasal administration. The intranasal naloxone comes in a blister pack. The device is intuitive and quite simple to use. If you have ever administered yourself a nasal spray to relieve decongestion, you can administer naloxone spray. A research study found that 90% of untrained users were able to administer intranasal naloxone successfully.

Treatment for Patients who are not Breathing and Those who May or May Not Have a Pulse.

Determining breathing is much easier than finding a pulse. If the chest isn't moving and there is no air coming out of the nose or mouth after waiting for a sufficient time (15-30 seconds), feel the person's neck for a pulse. If the patient has a pulse and isn't breathing, start rescue breathing if you are comfortable with it. (Note: If the person is breathing, there is no need to check for a pulse. In order to breathe, a person's heart must be beating).

Rescue breathing involves putting the person on their back, and tilting their head backwards to open their airway. If you have a plastic breath barrier or mask, use these for your protection. Pinch their nose closed, and give one breath every five seconds. Watch the chest for rise indicating air is going into the lungs. If you can't find a pulse and the patient still isn't breathing, assume the patient doesn't have a pulse and start CPR.

Post Resuscitation

Reassure a person coming back to consciousness from an overdose. Speak in quiet tones. Tell them they overdosed and that you gave them naloxone because their breathing was inadequate.

Do not be judgmental. They are likely to be confused from lack of oxygen. Help orient them by repeating what happened, telling them where they are, reassure them that they are with someone who cares about them. Stay with the patient until professional help arrives.

Where to Obtain Naloxone:

Naloxone in the intranasal form is now available for over-the-counter sale without prescription. However, it may not always be found next to the Tylenol. Many stores keep the naloxone locked up or behind the pharmacy counter. You may have to ask a store clerk if they carry naloxone. In Connecticut, pharmacists, who have undergone special training, are allowed to write prescriptions for naloxone. If you have insurance, ask them to write you a prescription so you will only have a co-pay instead of having to pay the full sticker price. Naloxone can also be purchased directly from the manufacturer or ordered online from the pharmacy or even a place like Amazon. Public health departments and harm reduction services such as syringe exchange sites also provide free naloxone and training.

911 And Beyond

Call 911

When you encounter an overdose, call 911 early. Get help on the way. When you call 911, your call is answered by an emergency dispatcher. Depending on where you live, the dispatcher could be in a large regional center with many operators, or they could be a single person sitting alone in front of a console in a small police department. While the dispatcher asks you what your emergency is, your address should already be appearing on the dispatcher's screen. The dispatcher will ask you a series of questions, but don't worry; responders should already be on the way.

EMS Care

Responders may administer additional naloxone if naloxone hasn't already been given, or if it has been given and the patient continues to have depressed respirations (slow breathing). If breathing is depressed, responders will use a bag-valve device, which consists of a plastic mask that they seal over the patient's nose and mouth, and an attached balloon type bag that they squeeze to send air into the patient's lungs. The administration of oxygen itself can sometimes revive an overdose victim if their opioid load isn't too much.

EMS will always recommend that rescusitated patients who have suffered overdose go to the hospital for monitoring and further evaluation. If they do refuse transport, it is important that they have someone to stay with them and make certain they don't re-overdose.

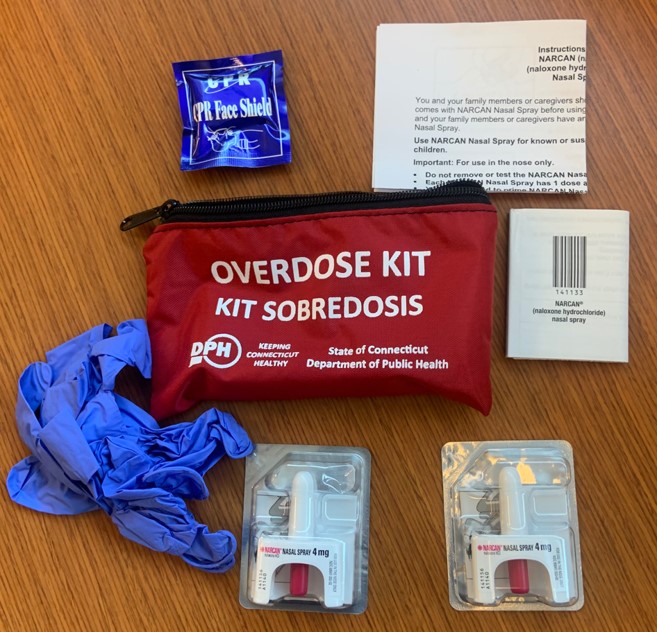

Naloxone Leave Behind

Many EMS services are now leaving behind Naloxone kits with patients, their families, and friends. The kits include not only naloxone and a face shield (if rescue breathing is needed), but information on where a patient can access help and other needed resources. Patients who do refuse may feel driven to use again, particularly if the naloxone puts them into withdrawal.

Hospital

The hospital offers further evaluation as well as an opportunity for intervention and treatment. For patients who have already been revived and are alert and breathing on their own, the hospital can monitor them for a few hours in a safe environment, and ideally can help evaluate their health, including mental health needs and direct to social services and treatment opportunities.

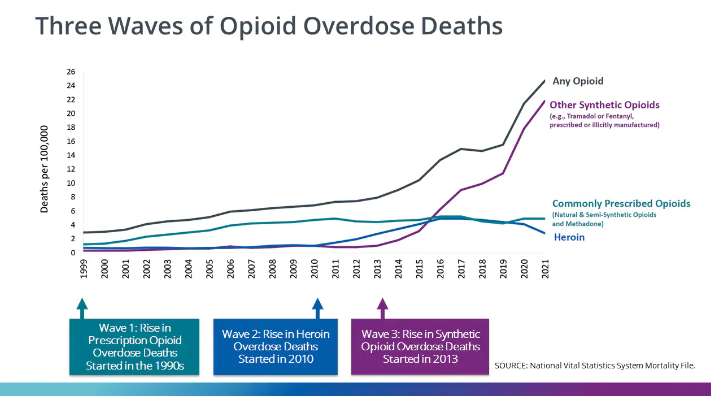

Fentanyl: The Present Danger

The first wave of the current opioid epidemic began in 1996 with the aggressive marketing of the prescription opioid painkiller oxycontin. As prescriptions rose so did addiction, overdose, and death.

The second wave of the epidemic began in 2010 when users switched to using heroin after an abuse-resistant formula of oxycontin was introduced. The reformulated pills made it harder for users to crush the pills into usable powder. Heroin was cheaper, stronger and more readily available. The death rate skyrocketed.

The third and deadliest wave of the opioid epidemic began in 2013 with the increasing adulteration of the heroin supply with illegally produced fentanyl. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid manufactured in laboratories, is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine by weight. The key factor is that fentanyl because it is so much more potent than heroin by weight directly affects the dealers' ability to evenly distribute fentanyl when mixing their batches with adulterants and filling small packages meant for street sale, or in pressing the powder into pill form.

The Cutting Process: Not a Science

Both heroin and Fentanyl are cut (adulterated) with substances like sugars, baking soda and other white colored powders. Adulterating the product produces more product to sell and helps to ensure that the product is not too potent. Typically, heroin was cut or adulterated to perhaps 50% heroin/50% cut. Fentanyl should be cut to 1% active ingredient, 99% adulterant if sold in a 0.1-gram package. That's easy to do if you are a multibillion-dollar pharmaceutical company with top scientists and labs with the latest state-of-the art equipment, but not so easy if you are a street level drug dealer doing the mixing on your kitchen table using a blender made for protein shakes. A 0.1 gram bag of cut "Fentanyl" contains 100 mgs of powder by weight. 2 mgs of Fentanyl is considered a potentially lethal dose by the DEA. How do you safely measure that at the kitchen table so that each bag you fill with a tiny spoon has only 1% fentanyl?

Unsafe Supply

The number one reason people are dying today of fentanyl overdose is that users cannot judge their dose. Even if you are the most experienced user, there is no way for you to tell the white powder you poured into your cooker (a small bottle cap sized container), mixed with saline and then drew up with your syringe and are now pushing into your vein is 1% fentanyl or 10% fentanyl, a dose that will kill you if you are using alone and no one finds you before your heart stops beating five minutes after the fentanyl stopped your breath cold.

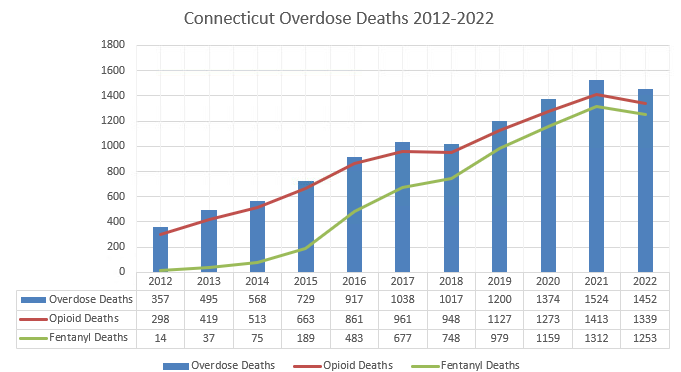

Death Numbers

In Connecticut in 2012, 14 people's deaths were attributable to fentanyl (5% of all opioid deaths). By 2021, 1312 people died of fentanyl poisoning, which represented 93% of all opioid deaths.

Source: Author created graph from Connecticut Office of Medical Examiner data

Nationally in 2021, according to the CDC, 88% of all opioid deaths involved fentanyl, and only 13% involved heroin. Fentanyl started its reign of terror on the east coast where powdered heroin was prominent. Most heroin users west of the Mississippi generally used black tar heroin, which is a sticky tarlike substance that has not been fully purified. Black tar heroin is typically smoked, but can also be injected. The economics of fentanyl, however, have spread fentanyl and the deaths westward. Much of the fentanyl in the west is coming in the form of pressed pills.

Counterfeit Pills

Years ago, if someone was worried that fentanyl might be in their heroin, they could seek safety in reverting to pharmaceutical pills like Percocet. The Percocet came from a pharmaceutical company so people could be certain that all pills had the same advertised strength. Not anymore. Dealers are buying pill presses and dyes for Percocet 30s and other common opioid pills, then pressing powder and fentanyl into counterfeit pills that look just like the originals. In 2018 law enforcement seized 290,394 counterfeit pills containing fentanyl. In 2021, they seized 9,649,551. In 2023, the number was over 79 million. Users cannot easily tell an illegitimate counterfeit pill apart from an authentic pharmaceutical grade pill. And like the fentanyl in the heroin bags, there is no way for a user to tell how much fentanyl is in the pill they just bought even if they know it is a counterfeit pill. 1% or 12%? An expected high or death? The DEA in 2023 found that seven out of ten fake pills tested in their lab contained a potentially lethal dose, up from four out of ten in 2021.

Source: DEA

Fentanyl Myth: Touching Fentanyl Can Kill You

There is no danger of merely being exposed to fentanyl. For fentanyl to harm you, you have to inject it, snort it or ingest it in significant quantities. It is not absorbed through the skin by casual contact. The skin is an effective barrier to powdered fentanyl. There are fentanyl dermal pads that are specially manufactured with a gel to enable absorption of the drug through the skim. It can take up to 12 hours for enough fentanyl to absorb through the skill to feel its analgesic effects. On July 27, 2017, the American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology had to issue a joint statement, Preventing Occupational Fentanyl and Fentanyl Analog Exposure to First Responders, stating that "the risk of clinically significant exposure to emergency responders is extremely low."

Why People Use Drugs and the Science of Addiction

People have used opioids since the beginning of civilization. In the third millennium B.C., the ancient Summarians who lived in what is now Iraq, cultivated the poppy seed and learned how to use opium derived from the seeds. They called it "the joy plant." In Homer's The Odyssey, the Greek hero Odysseus and his men--worn out from the ten-year Trojan War, filled with sadness for the loss of comrades, and beaten down by their long and difficult journey homeward--come to the island of the Lotus Eaters, where the inhabitants offer them a special plant to eat to ease their sorrow. Eating the lotus enables Odysseus's men to forget their heartaches.

In a YouTube video, Dr. Gabor Mate, the author of the landmark book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, has a conversation with Guy Felicella, a former user of drugs and champion harm reduction advocate. Mate asks Felicella, what the drugs did for him when he was struggling. He summarizes Felicella's response. "So the drugs gave you comfort, they gave you a sense of friendly acceptance, and they helped soothe your suffering…Those are wonderful things. In other words, the drugs weren't your problem. Your drugs were an attempt to solve your problem." He goes on to say, while drugs can cause problems, they are not the primary problem. We need to address the primary problem, the roots of the sufferings that drive people to seek relief in drugs.

People don't use drugs to become lawbreakers or to disrupt their families or communities or to threaten their own lives. People use drugs because the drugs work for what they need them to do, and that need can become so great, it overrules everything else.

The Science of Addiction

The American Psychiatric Association defines addiction as "a complex condition, a brain disease that is manifested by compulsive substance use despite harmful consequence." The Society of Addiction Medicine says addiction "is characterized by [an] inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one's behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response."

Opioids, which are among the most addictive substances, initially produce euphoria, an overwhelming response of dopamine in the brain, followed by an awareness of an ebbing of the drug and then for some, a preoccupation with reproducing the feeling. In time, some people's brains can become hijacked so people can no longer act in their best interest. These changes are so profound the damage can often be measured in images of the brain in the same way medical imaging can detect damaged hearts and lungs.

Today scientists believe addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is caused by a confluence of factors from genetics to environment, and mental health. It cannot be cured acutely, but needs long-term monitoring. Relapse is common. Even someone who has not used opioids for years can be triggered to use a gain. Addiction is not a character flaw.

Treatment and Recovery

In the United States only 22 percent of those with substance use disorder receive medication treatment. Our society too often treats addiction like a crime and punishes those addicted rather than helping them with treatment.

Drug addiction is a chronic disease. People with drug addiction should be shown the same empathy people with other chronic diseases are shown. Chronic diseases such as hypertension, asthma and drug use are treatable. Chronic diseases that are not treated often lead to preventable deaths. The goal of drug use treatment should be long-term survival not punishing anyone who is not 100 percent abstinent.

Treatment Programs

No single treatment works for everyone. The two main forms of treatment are behavioral therapy and medication-assisted. They can and should go in sync.

Behavioral Therapy

Behavioral therapy includes group and individual sessions focusing on modifying a patient's behavior patterns to help patients recognize situations that might lead to their renewed drug use. It teaches them how to avoid or at least cope with these situations. Patients learn to recognize what influences their drug use and work to improve their daily function, and give them positive reinforcement for behavior changes. Effective treatment should look not just at the drug use, but at the underlying pain that may have driven someone to find relief from suffering. No simple fix. No overnight miracle. But a journey.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) includes methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone. Methadone and buprenorphine are opioids that suppress the desire to use stronger opioids and depress withdrawal symptoms without providing the euphoria typical of opioids like heroin and fentanyl. They are difficult to overdose on. The argument has been made that people using MAT are just replacing one opioid for another. That may be true, but instead of opioids that kill and completely disrupt a life like heroin or fentanyl, methadone and buprenorphine enable people to be with their family, to work (and pay taxes), and lead productive lives. These opioids restore an equilibrium to the brain's circuits and can help lead to healing.

What to look for in treatment options.

There are many sad stories of people being swindled by drug treatment centers that lack sufficient medical oversight and trained staff. People who break small rules can be summarily kicked to the street. The group Shatterproof, founded by Gary Mendell, a father who lost his son to addiction, recently came up with a set of principles to guide people in choosing the addiction that is right for them or their family member. According to Shatterproof, quality addiction treatment should include: Fast Access to Treatment, Personalized Evaluation and Treatment Plan, Access to Medications for Opioid or Alcohol Use Disorder, Effective Behavioral Therapies for Addiction, Long-term Treatment and Follow-up, Coordinated Care for Mental and Physical Health, Additional Services to Support Recovery, and Routine Screenings in Every Medical Setting.

According to the CDC, opioid use disorder cost the country $1.02 trillion in 2017, counting law enforcement, health care costs, substance use treatment, loss of life and productivity. $14.8 billion of that was spent on law enforcement, while only $3.5 billion was spent on treatment. We need to reorient our priorities.

Harm Reduction: Keeping People Alive

I attended an overdose prevention conference. A man named Mark Jenkins talked about harm reduction. He struck me as someone speaking the truth. He said the job of harm reduction was about saving lives because dead people aren't able to make good decisions. I began to see Mark and the people he worked with out on the streets of Hartford. Sometimes they would be at overdose scenes before me or arrive shortly after. If a lay person had given naloxone and was still there, I would ask them where they got the naloxone and they would often answer they'd gotten it from Mark or from his organization--the Greater Hartford Harm Reduction Alliance.

Mark's group eventually opened up "The Drop" on Albany Avenue in an area where drug use and overdoses were common. People go to this drop-in center for syringe exchange, to get naloxone, or help with services if they are ready for that. The place also has a shower they can use. They even started serving sandwiches. Some people just like sitting in there and talking. Eventually Mark hired a nurse to help people with their wounds and give vaccines and do medical testing. The Drop is a safe place for people who often fall through the gaps.

In Harm Reduction and Abstinence Based Treatment, "Bridging the Gap,'" Van Asher describes harm reduction as a life raft that rescues people in the sea. Harm Reduction helps some people make it to shore (treatment), and for others who chose to live in the sea, it keeps them from drowning. Harm reduction bridges the gap between active use and treatment.

Typical harm reduction services include counseling, naloxone distribution, syringe exchange and safe use supplies (cookers, saline bullets, alcohol wipes, cotton to filter out impurities, clean tourniquets), fentanyl test strips and drug checking services, safe sex supplies, safe smoking supplies (safe mouth pieces, filters to prevent burns), antibiotic ointments, wound treatment, vitamin C to help prevent infections and promote healing, food, clothes, and even from organizations like Mark's, tents and sleeping bags for the homeless if Mark's group is unable to find them shelter.

Harm reduction is concerned first and foremost with saving lives. Moral judgements are cast aside. The message is that people matter. Harm reduction enables people to use safely until they are ready to quit. It casts no judgement. Instead of promoting drug use, harm reduction ultimately means less drug use and more people getting into treatment. It means less death.

Overdose Prevention Centers

The Harms of Stigma

Naloxone will not save you if you use alone. I have found naloxone on many of the overdose death scenes I have been on. Often the naloxone is within reach of the body. Ninety-one percent of people who die from opioid overdoses die using alone. Why do they use alone? Stigma. Stigma causes people to hide their addiction. The stigma of being an "addict" implies that person is to blame for their actions. The words we use to describe someone not only affect how we view that person, but how that person comes to view themselves. Stigma prevent people from seeking help.

Stigma means stain. When we stigmatize someone, we put a stain on them. It suggests not just moral judgment against a person, but it also inspires fear in others, works to isolate people, and criminalizes their behavior. The user becomes a stereotype and not a person. A "dope fiend" is not someone considered capable of positive human interaction.

The World Health Organization (WHO) studied stigma in 14 countries to determine what conditions (homeless, AIDS, obesity, mental disorders, alcoholism, criminal record for burglary, etc.) were most likely to be stigmatized. Drug use was number one.'

Science has shown that social pain is felt in the same area of the brain as physical pain and thus responds to pain medicine in the same way physical pain responds. In an opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Nora Volkow cites a study in which lab rats chose interacting with other lab rats over self-administering drugs, but when they were punished with electrical shocks for their social interactions, they reverted to drug use. She concludes that stigma "spurs further drug taking."'

Ending stigma could change the course of this epidemic. People who use drugs are human beings knocked off course by a larger epidemic not of their making. None of them set out to become addicted to drugs, to become homeless, lose their families or their lives. An addictive gene, an accident, a doctor's prescription, an innocent experimentation, a history of sexual abuse or mental health problems, diagnosed or undiagnosed, so many factors were behind their use. We must stop driving people into the shadows or locking them because we don't like their disease. Drug treatment, housing, health care, job support and human empathy and love will go farther than hurtful words and prison bars. As humans, we all belong to each other.

The War on People

If telling people just say no or you are going to end up dead or in jail worked, then there would be no opioid epidemic today. If putting people--many addicted to drugs themselves--in jail for life for dealing $3 bags of fentanyl worked, there would be no fentanyl available to buy on the street. Unfortunately, these strategies fail. Demanding abstinence and locking up people for low-level drug offenses has done nothing more than fill up our cemeteries and penitentiaries.

Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas in a landmark ruling in Robinson v. California, wrote, "It is cruel and unusual punishment in the sense of the eighth amendment to treat as a criminal a person who is a drug addict." You cannot treat a disease as a crime and expect to eradicate it.

The War on Drugs has failed. After 50 years and trillions spent, drugs are cheaper, more lethal, and more readily available than they have ever been. And before anyone claims the war represents the moral high ground, we need to look at how the war started and understand that the motives were based on politics and not reasoned policy.

John Erlichman, President Richard Nixon's Chief of Staff, confessed to a journalist the true motivation behind the war on drugs, which began in 1971 when Nixon declared drug use "Public Enemy Number One." "You want to know what this was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I'm saying? We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did."

In 2006, while African Americans represented only 15% of the country's drug users, they represented 74% of those sentenced to prison for a drug offense. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse 85% of the prison population either has a substance use problem or were jailed for crimes involving drugs or drug use. A conviction on someone's record can make them ineligible for public housing, student aid, and deny them job opportunities, making it very difficult to integrate back into society.

Do these drug laws have any effect on the availability and use of drugs? No. A recent research study in the International Journal of Drug Policy suggests that new laws charging drug dealers with homicide will have little effect and might even have the unintended consequence of deterring people from calling 911 to report an overdose. Many dealers support their own habit by selling to others in their circle. Past research found that 70 percent of state prisoners and 59 percent of federal prisoners arrested for drug trafficking were drug-dependent in the month before they committed their crimes. Knowing that selling to someone who overdoses could lead to imprisonment, one friend might leave an acquaintance overdosed and alone rather than risk summoning help that could lead to a twenty-year prison term.

Overdose deaths are five times higher today than they were in 2001. And much of the early crisis was from overprescribing and then cutting people off. We have adopted safeguards and prescribing it down, and physicians are aware of the dangers of not properly tapering people off opioids. The deaths are catastrophically higher today not because of current prescribing but because the drug supply is toxic. People are being poisoned. If you had a daughter who was addicted to fentanyl, would you rather have her buying her drugs in an alley and shooting up behind a dumpster or have her getting her safe supply from a government regulated health center and using in front of a health care provider who could talk to her about getting help? Safe supply will save lives.

The World Health Organization has called for decriminalization of street drugs. The United Nations Development Programme has said "Laws criminalizing drug use/possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use impede the access of people who use drugs to basic services, such as housing, education, health care, employment, social protection and treatment."

The choice is ours. Continue with the insanity of the Drug War and its devastating effect on our citizenry. Or recognize drug use as a disease and a public health issue and treat it accordingly, with empathy and evidenced-based policy, not politics.

Credit: Today I Matter

The Friends and Family Guide to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic

Including How to Recognize and Treat an Overdose

A practical and compassionate guide to understanding and addressing the opioid crisis.

The opioid crisis in the United States continues to kill Americans at an alarming rate. Over the past two decades, annual overdose deaths have skyrocketed, growing from roughly 20,000 per year to over 100,000 per year. In this deeply informed and compassionate guide, Peter Canning shares the devastating realities of the opioid crisis from the perspective of a seasoned paramedic and advocate. This essential resource provides practical tools to recognize and respond to overdoses, access life-saving treatments like naloxone, and navigate the complex landscape of addiction and recovery.

Canning humanizes the crisis through poignant stories of individuals and families grappling with the ripple effects of substance use. The book offers a broader understanding of the epidemic's roots, including the rise of fentanyl, the science of addiction, and the transformative potential of harm reduction strategies. Canning explains how to recognize the signs of overdose, the risk factors that increase the likelihood of overdose, and the precautions that both people who use opioids and those who care about them can take. With extensive experience as a paramedic who responded to countless opioid overdoses, Canning explains what to do in case you discover someone who has overdosed on opioids.

For anyone trying to help a loved one manage opioid use disorder, the process can be overwhelming, and the stigma that accompanies substance use disorder makes it even harder. Whether you're a concerned citizen, a family member, or someone directly impacted by the crisis, The Friend and Family Guide to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic equips you with the knowledge and empathy to take meaningful steps toward saving lives and fostering understanding in your community.

From JHUP

Book Update # 1 Medetomidine

Medetomidine, an animal sedative, appears to be replacing xylazine as a significant adulterant in fentanyl and perhaps other drugs. According to reports from Philadelphia, one of the areas where xylazine first gained prominence, medetomidine was in 87% of samples of fentanyl in November 2024 compared to just 42% of samples which contained xylazine, while at the beginning of the year xylazine was in 100% of the samples. Why is this happening? Pennsylvania rescheduled xylazine as a class III controlled substance in May of 2024, making it harder to obtain.

Drug dealers, who I believe mixed xylazine into fentanyl because it is so much cheaper than fentanyl, are simply moving on to the next similar substance. A Notes From the Field Report from the CDC says medetomidine like xylazine provides sedation, but unfortunately leads to even more severe withdrawal experiences than xylazine. On the other hand, it appears to not cause necrotizing wounds like xylazine does.

How this switch will affect fatal overdoses in uncertain. When xylazine showed up, people were scared that it would lead to increased fatalities, but it appears to have had a protective effect. Rather than adding xylazine on top of fentanyl, xylazine replaced some of the fentanyl thus each bag, containing less of the lethal drug, appears to have led to fewer overdoses. Additionally, by providing extended sedation ("legs") people use less often, resulting in fewer opportunities to overdose. In Connecticut as xylazine rose in the drug supply, deaths went down.

I don't have official numbers on how prevalent medetomidine is in Connecticut today, although I do know, according to the state health department, one of the fatalities in December 2024 tested positive for medetomidine, and early drug checking data shows increasing amounts beginning last year.

While fatal overdoses declined significantly in the last six months of 2024 in Connecticut, nonfatal appear to be increasing through each of the first six months of the year according to EMS data. No solid information yet on whether fatal overdoses are also up, although anecdotally, I believe they are. (Why they declined and why they may be going back up is open for speculation. My best guess is an increase in fentanyl purity.)

Life xylazine, medetomidine, is not an opioid. It will not respond to naloxone. But it seems unlikely that either of these animal sedatives are stopping people from breathing on their own. If someone takes fentanyl with medetomidine and they stop breathing, naloxone, if given in time, should still restore their breathing, while it may not affect their sedation. Sedation is fine as long as they are breathing. We don't care if the patient wakes up, we just want them to be able to breathe on their own. The sedation will eventually wear off.

What does this all mean? We have an everchanging drug supply as dealers try to make more money, utilizing the cheapest available chemicals, and evade crackdowns. We can only hope that the newer and next chemicals will be less toxic, but that thinking is clearly wishful.

Donate

Donate to these three groups or any of the other many fine organizations dedicated to ending this crisis.

We are a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization established in memory of Timothy Lally. Our mission is to reduce the stigma and shame of mental illness and addiction, and to promote the physical, emotional, and mental health of our community. We are committed to promoting and advocating for the physical, emotional, and mental health of all in our communities. We are dedicated to speaking out and educating the public at large about recognizing, preventing, and treating these illnesses. In addition, we support positive health through the arts, education, sports, and other activities that enhance each individual's self-image and sense of well-being.

***

Shatterproof is a national nonprofit organization dedicated to reversing the addiction crisis in the United States.

***

Connecticut Harm Reduction Alliance

Standing in the Gap